Visit Our Online Shop

Follow Us

Diary of a War Dog

In the second of her series looking at the role of animals in war, vet nurse Meg Gardner looks at life in the trenches for the men and dogs of Twenty-two Company King’s Fusiliers.

An uncompromising tale of life on the front line in 1916, as told from the perspective of the dogs who lived and worked alongside the soldiers of the British Forces.

A tale of loyalty and friendship, hardship and loss.

As both men and dogs face the horrors of warfare, an unexpected arrival in the trenches show both dogs and men the value of compassion.

Warning: The following passage contains graphic descriptions of war and death of both animals and people. Reader discretion is advised, and content may not be suitable for children.

THE SOMME, FRANCE 1916.

Two years ago, if someone had told me that life would find me hundreds of miles from home, elbow deep in mud, with nothing to keep master James and I company but savage wind and rain…. why I’d have said they’d had too much scrumpy cider from the apples in our farm orchard. I still dream about the farm…. now and then. It seems my dreams these days are mostly about running to escape the snipers and insurgents. Sometimes I dream that I jump the parapets of the frontline trench and I’m heading at top speed for the reserve trench. I’m almost there, I look behind me as I run, but I can’t see my master, where is master? I can hear him shouting, but all I see is smoke and fire.

“Master James,” I bark. “Hurry, you must hurry. The gas is coming, the gas is coming!!!”

Then I wake up.

Master James strokes my head. His words comfort me. For a moment I don’t know where I am… I’m still in my dream.

“There now, silly old thing,” he says.

Master dreams too, I don’t know what he dreams about but sometimes he shouts…. it scares me. Then he sobs… sometimes I hear him call for someone. I lay a paw on his face and lay myself down upon his chest, and I stay with him until he is calm.

“There now, silly old thing,” I mumble.

It can be lonely some nights when master and I are on trench patrol. It depends on which part of the line you get sent to, but if you are lucky and get to guard the work parties, you can often get scraps of bread and jam from the infantrymen. They sneak some of their rations up to the line and pass a bit to us as a thank you…. you know, for keeping them safe. Most nights master James and I guard the communications trench. It’s not a bad job, but you need to have your wits about you mind. Jerry likes to creep over no-man’s-land when he thinks you are not paying attention and throw a grenade or two into the trench. Some nights, they set us mines and tripwires, but that means approaching the dog patrols. I caught one of them three nights ago. I’d have brought him down too had it not been for losing my footing in the mud. Oh, I sent him scurrying back to their trenches alright, with a nice imprint of my teeth in his backside as a souvenir.

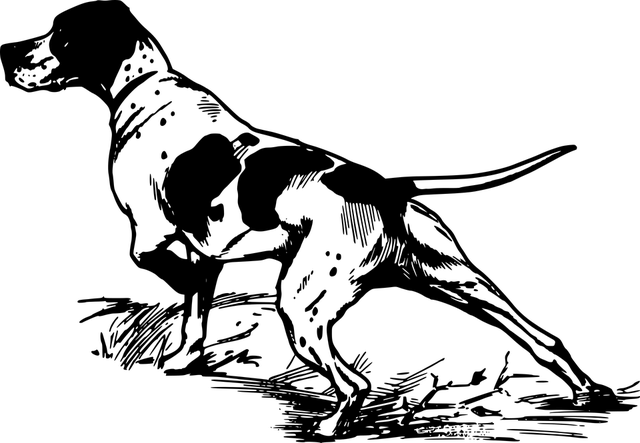

My name is Reuben by the way. I am a German Short Haired Pointer, but we’ll keep that to ourselves. There are some around here who would take a stick to me for that, mad I know…. a dog can’t help his heritage. Most of the soldiers here wouldn’t know one breed of dog from another, so I’m just a Pointer, for all those who have got an interest to ask.

There are six dogs in Twenty-Two Company. There is Jess, she’s a black Labrador. Intelligent, willing; she knows every inch of this trench line. Then there’s Curly the wire-haired Jack Russell; a bloody nuisance, always in trouble. The only thing he’s good for is ratting. Still, comes in handy when food is rationed. Then there are Noah and Moses, the two red and white Border Collies. They belong to the captain. Oh, they look innocent enough, but they’ll bite you soon as look at you. The smiling assassins master James calls them. Lastly, there is London Charlie, he’s a mixed breed. Mother was an English Bull Terrier, and father was, well…. no better than he ought to be, a fly by night. London Charlie inherited his mother’s domed white nose and a black patch over one eye, and as for the rest of him… well, one can only guess. His name came about because there used to be two Charlies in the trenches. You can’t have two dogs in the trenches with the same name, so because he and his master came from London, he became known as London Charlie. The other Charlie was a fantastic dog, sharp as a trench knife and as fast as a bullet. He could sniff out anything, and he could run all day long and still have enough energy for patrol. That’s the thing with Springer Spaniels, they can just run forever, they never tire, and he was always willing to work, even in the rain. His willingness was to be his undoing…. in the end. Charlie met his maker one day last autumn whilst searching for mines in no-man’s-land. He caught a scent from over the parapet of the trench and shot off like lightning, keen to get after Jerry. Master John shouted at him to wait, but Charlie was on the scent. He ran light, over the divots of the shell holes, darting left by the burnt oak. Master John shouted and shouted; his hollering caught the attention of the rest of us back in the trenches. Charlie jumped the barricade, he had Jerry in his sights, and he kept running. He knew where to run to the right to avoid the snipers, but he hadn’t banked on them laying new mines just to the left of the communication’s post. I don’t think he knew what hit him. I swear my heart froze as I saw that mine go up. Poor master John, he cried for days. I don’t think I ever saw him so sad.

Even though we only had one Charlie left in the trench after the accident with the mine, they all still called him London Charlie… it kind of suits him.

The days are all the wrong way round here in the trenches. In the daytime, we rest, save the ‘stand to’ at the first hour of dawn and the last hour of dusk. This is when we take it in turns, to be posted as the lookout. It’s lonely and dangerous up on the fire step which is a raised platform of wood and sandbags or a shelf of compacted mud. Here we have a look-out post which looks out over no-man’s-land. The viewing port is just about big enough to put a rifle through. At every fifth post in our sector, there is a machine gun. It’s always better to be assigned to the machine gun look-out, much better chance of survival. Few Jerrys are prepared to take their chances against machine guns. A Lee Enfield rifle relies much more on the accurate shooting of the infantryman at the end of it. Snipers always seem to have better luck picking off the riflemen.

Night-time is when we do most of the work. After dark is a good time to move men and equipment…. less visible, see. Trenches and latrines get dug by lamp light, and our boys need watching and guarding as they go about their duties. Some duties get done in the day, but for the most part, we rest. When battles happen between opposing enemy trenches, they are fierce and terrifying. Daytime is a good time for launching mortar attacks. The good light assures accurate targeting. For all that the fortresses of wood and barbed wire can protect us from frontal assault, nothing can protect us from the carnage raining down from the skies. That low whistle that precedes a mortar attack is a truly terrifying sound when you are sat in the trenches.

Trench life is all about routine. Duty consists of twelve days on, four days off. Eight days you spend in the frontline…. you don’t sleep much. It’s not full-on fighting all the time, but when the attacks happen, it’s the frontline that gets the worst of it. Then you work four days in the reserve and back trenches. We rest as much as possible, but there are always things to do, and of course, we are always on standby to fill in on the frontline. We then have four days leave from the trenches which are either spent at base camp or some choose to take accommodation in the local towns and villages. A lot of the taverns and boarding houses don’t allow dogs, so master and I stay at base camp when we are on leave.

April 1916.

Sunday night had been quiet, and master James and I had managed to knock off early with the hope of getting a couple of hours extra sleep.

London Charlie decided to wake me up at some ungodly hour whilst on his way to the fire step for morning stand to. I’d just got myself comfortable in between two kit bags when the blundering oaf came along sniffing and rooting around for some scraps of bully beef.

“There ain't none, and I’d be grateful if you’d clear off and let me sleep,” I growled at him.

He licked my master’s face. Master James didn’t seem to mind being woken up. He opened one eye, then shut it again, and reached out a hand to stroke London Charlie on the head. That’s it, the damn impertinence of it! Who did he think he was? He was supposed to be on duty with his master.

“Clear off!” I snapped at him. “Go and do your duty soldier, this is our rest time, we’ve been up all night on patrol.”

London Charlie turned and left. I pushed my head up under my master’s hand and nestled myself down by his side.

“You silly old thing,” he uttered, patting my head before falling asleep again.

Two more days and we’d be on leave. I sighed as I settled down to sleep. Soon I found myself back on the farm running the cattle up from the bottom meadow for evening milking. Master James patting the bony old rump of Duchess, the matriarch of the herd. She’s always last through the gate, but she’s earned her right to be slow after all these years. The sun hangs low over the apple orchard as milking is finished, and master James tells me to run the herd back to the bottom meadow. Dusk settles and before long dark sets in, but I can hear shouting, it’s master… so loud, he’s shouting…. I wake up. It’s master, he’s shouting in his dreams again. I lay across his chest until he calms. I lick his face and his hand raises to stroke my head.

“Good boy,” he said. He won’t remember that in the morning.

“Come with me,” I mumbled through my jowls. “I’m just running the cows back down to the bottom meadow.”

“Fetch Duchess, Reuben,” he said suddenly from nowhere in his sleep. At least he’d stopped dreaming about the war.

May 1916.

Jess and I were excited. We were off to base camp on leave for four days’ rest. We had to walk to base camp as the transport truck had broken down again, the second time this week; still, the weather was good, so a good walk would be welcome, even our masters didn’t seem to mind, anything to be out of the trenches. Nothing could spoil the mood today, there’s nothing quite like shaking off the shackles of duty.

Jess and I took it in turns to run ahead. Master James and master Alfred walked at leisure. With no march beating out a rhythm to walk to, they smoked cigarettes and laughed as they walked. There were lots of things to sniff and smell along the way, and Jess and I enjoyed each other’s company, playing tag and rolling around in play. We headed up the hill from the woods, the road winds around and curves into a blind bend at the brow of the hill. We trotted side by side. It was a competition now to see who could trot the fastest. I looked at her, she looked at me. I’ve got longer legs, but she moves quicker. She upped the pace to compensate for my lengthy stride. I pushed through from my back legs, extending my shoulders, my stride increasing. Suddenly Jess stopped dead. I turned around to see where she was; she was rooted to the spot, sniffing the air…. something was wrong. Our masters were still some distance behind. They’d stopped to talk to a cavalryman. He was riding a big black horse. I looked up ahead, but I couldn’t see any danger. There was something on the air. Jess was never wrong when it came to danger. Her nose was high in the air like there was something she was catching, but she couldn’t quite figure out what it was. I took a step forward; Jess gave a sharp bark. I stopped again. I guess two noses are better than one, so I began sniffing to see what I could smell. Something was catching at the back of my nose, but what? I moved forward; Jess looked at me anxiously. I slowed my gait and lowered my head to see if I could catch a scent from the ground. I stopped, lifting my head again I could hear something in the distance from around the bend, it was a marching company of men, they were some distance off, but they were advancing. I didn’t know what was wrong, but something was…. and they were heading straight towards it. Jess joined me at the brow of the hill, we looked at each other and then down the hill towards our masters, we must warn them. Jess began to bark. The cavalryman had moved off and was now trotting up the hill towards us. I started to bark as well, hoping to frighten the horse into staying away, but it just kept coming. A breeze rushed past me, and the scent was unmistakable; that metallic tang, the smell of explosive…. it was a mine. Our masters were paying no attention, smoking cigarettes and laughing. I can only do what I’m trained to do, I’m bred and trained to point, pointing means danger. Jess was franticly barking. Surely, they must look up the hill shortly. I stood tall, head erect, back long and low, with my back legs broad and tail held rigid behind me, a front leg lifted into the air, my whole body poised in the direction of the danger. It wasn’t working, master James wasn’t looking, and the horse was getting closer and closer. Jess was beside herself; they were taking no notice of us at all. The horse trotted past us, neither rider nor horse paying us any mind. We watched as the horse approached the bend. Back down the hill master James looked up to where Jess and I were standing, Jess frantically barking, me on point. He looked at the horse and rider as they started to disappear around the bend. He dropped his cigarette and started to run up the hill, yelling at the top of his voice, but it was too late. Everything at that moment stopped. I could hear master’s calls, but they were just echoes in the dust. Footsteps, running, screaming, the cries of both the cavalryman and the horse. Confusion took over. The advancing party of infantrymen reached the scene. Soldiers stood in disbelief, knowing that moments later it would have been them. Master ran by me, out of breath from running up the hill, but the adrenalin of his fear still powered him on. The horse lay in the road, its front legs blown away by the landmine, but it was still alive. The rider was trapped beneath it. It took three men to drag the lad out, he was screaming. The horse thrashed and thrashed, the white of the bone of its shoulder blade was sticking out of its flesh, its back leg was shattered, and was flailing as it tried desperately to get to its feet. I’d never heard a horse scream like that before. No one could get a clean shot off to put it out of its misery, they tried, over and over. Bullets went into its neck, and it's back…. some missed altogether. In the end, an infantryman shot it through the heart. That wasn’t a clean shot either, but it was sufficient to make it still enough that they could shoot it in the head. Jess and I could only stand back from the crowd and watch.

The cavalryman was badly injured. Some of the soldiers removed their jackets to try to make a stretcher to put him on; his cries will haunt me for the rest of my days. The soldiers were trying to comfort him, telling him over and over he’d be ok. He kept crying out the name Oliver, I think that must have been the name of his horse. They tried to shield him from the sight of the animal’s broken dead body.

Eventually, the cavalryman was taken away and the remaining men of the trench relief continued their march to the trenches, the mood of their march now sullen and silent. The road was empty once more except for the four of us. We all sat on the grass just staring at the horse laying in the road, its destroyed and bleeding body now lifeless and still. Master sat smoking a cigarette, his hand shook. I sat beside him and pushed myself into his side. I licked away a tear from his face. He took my head in both hands and looked into my eyes.

“You tried to tell me didn’t you fella,” he said. I licked his nose; he smiled but more tears came.

July 1916

Our sector had seen fighting fiercer than ever before. The horror had started one Saturday morning, two weeks ago since. Men, so many men had climbed the parapets of the trenches never to return, with carnage and brutality on a scale that I had never thought possible.

Master and I had been assigned to medical duties to assist the mercy dogs of the red cross who went out into no-man’s-land in search of the wounded. Whilst master attended to one man, I would search for the next. If I found a soldier alive, I would return to master so I could lead him to where he had fallen. I soon learnt to tell the difference between the silent injured, and those who were dead. I carried first aid supplies in a pack on my harness. If a soldier were able to, he could use the field dressings and bandages to dress his wounds. Often, soldiers were unable to help themselves, so I would lay across them to keep them warm until help arrived. Sometimes, the men would be in too much pain and couldn’t bear to be touched, so I would just sit beside them as company until master came. I could never understand what they were saying to me, but they were always grateful I was there. Sometimes, I was the last thing they saw.

Popular fiction would have you believe that death on a battlefield is noble. Nothing could be further from the truth. Men scream and cry as they die. They wet themselves and cry out for their mothers, terror and fear consume them as they bleed out. Often, wounded men sit paralysed, rigid with fear, or they mutter incomprehensively…. shell shock they call that.

The men of Twenty-Two Company carefully lowered the wrapped bodies into the holes that had been dug in the fields preceding the trench lines. With so many casualties, orders were to dig holes deep and fit as many in as possible. The last body placed into the hole was that of Private Peter Thompson. Peter Thompson was London Charlie’s master.

“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord, and may perpetual light shine upon them,” said the company chaplain as he made the sign of the cross.

I sat at my master’s side as he paid his respects at the roadside. He picked some wildflowers that grew alongside the hedgerow and laid them on the mound of earth. Soon, the captain came, barking orders at the remaining men to get back to their duties. I don’t think he means to be unkind; I think it’s just his way of dealing with it. Master James was angry, how could God let this happen? The chaplain tried to comfort the men, but there was no comfort to be found. Master and I got up and began our way back to the trenches. I stopped and looked behind me. There, sat on his master’s grave was London Charlie. He laid down, whimpering softly. He had no one to be angry with. What would become of him now? I wondered. Master James called me, and I turned and left… it had begun to rain.

For three days, London Charlie didn’t move from his master’s grave, even the rain did not deter him from his vigil. We had just returned from the medical post when I caught sight of him. He was laid on the mound of earth, shivering. Master was about to head down the lane toward base camp when he stopped to light a cigarette. He glanced down the lane to the rows of wooden crosses that had been dug into the earth to mark the places where fallen comrades lay. He saw London Charlie sat upon the grave. He took a draw on his cigarette and looked at me. I barked and looked down the road toward London Charlie.

“Looks like we aren’t the only ones missing our friends eh Reuben,” he said. He took another draw on his cigarette and then dropped the half-smoked remnant on the floor, flattening it with his foot. I fidgeted. I looked at London Charlie, then looked at master James.

“Come on boy,” he said.

We made our way down toward the grave site. London Charlie sat up as he saw us approach.

“There now London Charlie,” said master. “You can’t stay here old fella. Look at you.”

London Charlie shivered, he was wet and cold and hadn’t eaten or drunk for days. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a dog look so sorrowful. Master took off his trench coat and wrapped it around him. He took a piece of dried biscuit from his tunic pocket and offered it to London Charlie. He took it with gratitude.

“No one thought about you did they eh, all too busy fighting this damn war. Come on boy, you come with us.”

Master James stood up and gently took London Charlie by his collar. London Charlie took a few steps, then looked back at his master’s grave.

“It’s ok boy. He’ll still be here… we’ll come and visit…. promise.”

London Charlie turned and walked slowly beside master and me. Seemed master James had two dogs now.

September 1916.

The fighting continued into the autumn, and our company was sent further up the line to relieve the infantry units near Theipval. A village not far from the town had been a German stronghold. Fighting to liberate the village had been long and drawn out; casualties had been high, and now command wanted to send in the dog patrols to search for any hidden mines and explosives before handing back the village to the French.

The truck pulled up outside a tavern and we jumped out. We all wore collars and leads for this mission until being given orders otherwise. There wasn’t the usual banter being exchanged amongst the soldiers, a feeling of apprehension hung in the air as the men unloaded kit bags and equipment from the truck.

We were the first to enter the village since the infantry units had left and it was our job to sweep the village, root out any threat, and annihilate any remaining enemy resistance. The village told its own story as we walked the empty and now silent streets. Craters and shell holes lined the road. The bodies of German soldiers lay scattered about the village, and as we turned down a narrow lane, we saw the bloated body of a cavalry horse laying in a ditch by a well. Birds pecked at the eyes of both the soldiers and the horse. The buildings were derelict and had been ransacked, bullet holes lined the walls, rooftops were caved in, and broken timbers hung from the gables. Fires burnt here and there, and everywhere the stench of death carried on the wind.

I walked close to master James, and in turn, London Charlie walked close to me. I looked behind me. Jess looked nervous, she sniffed the air as she walked, dropping on her haunches every time she heard a noise. Even Curly the Jack Russell stayed close by master Jack. The captain walked ahead of me and London Charlie. Noah and Moses, walked at arm’s length ahead of him, sniffing the ground as they went.

We reached an old farmhouse. The house was little more than a ruin, but the stable block that lay on the other side of the courtyard had remained intact. The captain decided that we would make the stables our command post from which to coordinate operations.

Master James took wire cutters from his kit bag and put them in his pocket. One common Jerry trick was to leave trip wires attached to grenades before retreating. The tripwires were deadly, and it was so easy to run into them unknowingly. Almost impossible to see, and with virtually no scent to speak of, they were not for the inexperienced. London Charlie had never been on an explosives mission before, and I would be lying if I said that I wasn’t more than a little nervous at having a raw recruit with us. London Charlie was always keen to please, but he lacked the delicacy required for this job; you can’t just go blundering in, bounding around like a big oaf. I looked at master, oh how I wished Jess had been my partner for this operation.

“Now then Reuben, we have a rookie on the mission this morning, so it’s up to you to teach him,” said master.

As if reading my thoughts, master James checked that the clasp to London Charlie’s lead was secure and that his collar was no more than two fingers tight. He unclipped my lead to free me. I waited and sat patiently by master James’ feet. London Charlie looked confused, he couldn’t understand why I was free, but that he was still secured to a lead; he looked up at Master James.

“Not just now old fella, you’ve some learning to do. Don’t want you rushing off and blowing us all to kingdom come now, do we,” he said.

Master James stroked his face. London Charlie didn’t understand, but he trusted master and was obedient to the lead.

We moved out toward the village, Jess, Curly and the two collies now free to work up the scent. The two collies ran ahead. I took the left flank; Jess took the right as we came out of the farmyard and headed for the village square. Curly was an old hand at explosives, he could sniff out grenades better than any of us. He skirted around the men, nose to the ground. London Charlie began to get agitated and pulled against the restraint of the lead, but master held him tight, checking him back in when he tried to get too far ahead. He panted with excitement.

It wasn’t long before we came across our first find. Captain shouted at the men to stay back. I turned and looked. Up ahead Moses was laid flat on the ground, his nose outstretched, his signal for danger. The captain called Noah back to his side. Noah sat watching anxiously as his brother held his position. The remaining handlers raised their hands and Jess, Curly and I all sat where we were. London Charlie strained on the lead to see what was going on, but Master James checked him back and put him in a sit position, telling him firmly to stay and be quiet. He pricked his ears and waited. Two soldiers quickly moved forward and cautiously approached the area where Moses had stopped. The other infantrymen of the unit slowly moved out in a fan shape, looking down the sights of their rifles as they went. It could all just be a game. Sometimes the enemy would set trip wires or mines, wait until the unit moved in to defuse them and then ambush them, or detonate another device nearby. Tension filled the air. London Charlie began to paddle with his front paws, seems he didn’t quite understand the gravity of the situation. He made grumbling noises. Master James took his muzzle and held it firmly, telling him no. Should he start to bark, he would give away our position, and that could mean death for us all. I glared at him from where I was. A signal went up, the men had found a mine. We held our positions until we were sure no enemy was close by, and then the area was cleared until the mine was made safe.

We found a total of six mines and one unexploded shell that morning, and although one could never say for sure that no more mines remained, the village was declared safe for civilians to return. People were warned to keep away from the outlying areas and drainage ditches in case of further hidden devices.

With work over, we dogs took some recreational time out to play. London Charlie was grateful to be off the lead at last and sniffed the stash of deactivated weapons we had found. It was going to take some training for him to work as an explosives dog, and I had a feeling it would be many months before he could work off lead. Personally, I think one should always work to one’s own strengths, and I believed that for London Charlie, that strength was guarding.

November 1916.

Winter came early, with bitter winds and deep snow drifts making fighting impossible. Blizzards blew across the region, leaving visibility in no man’s- land down to no more than a few yards. The landscape was barren and frozen. Water supplies froze and with the ground as hard as iron, no digging or trench repairs were possible. At times, temperatures were unbearably cold and for dogs and soldiers alike, it was a constant battle for food and warmth. Our masters did all they could to keep us sheltered. Some of the men gave us jumpers or wrapped their scarves around us for warmth. Master James, London Charlie and I all shivered. We would sit, wrapped in a blanket, huddled together to share warmth while we rested. Sickness was rife amongst the soldiers, and I was worried. Master had begun to cough two days ago and last night he had no mind to eat his supper. The ground in no-man’s-land was solid and rutted, but in the trench line, the mud remained stinking in places with the cess from overflowing latrines as the ground was too frozen to dig further pits.

One morning, a young soldier hadn’t returned to the dugout following his duty at the stand to. Master James and I went out to look for him. Master wrapped his trench coat tightly around himself; he was coughing again. The snow began to fall as we walked. We reached the fire step to see the young boy still at his post, looking out through the gun port.

“Hey… mate,” said master James. “You can stand down.” The soldier didn’t reply. Master stamped his feet impatiently, blowing into his hands and rubbing them together. I sat beside him, shivering. “Mate…. Corporal Mason,” he said, shaking the young lad by the shoulder. He dropped his hand abruptly and took a step back, rubbing his face. “Jesus Christ,” he uttered.

I didn’t understand. I gave a small whine. Why wasn’t he moving? I pawed at the corporal’s trench coat, then I sniffed him…. I knew that smell.

Gently, master leaned the young boy backwards. The boy stared straight ahead, the blue of his eyes opaque, the whites of his eyes frozen. Master bowed his head and said a prayer. Suddenly, something moved from inside the corporal’s trench coat. I looked at master James, but he was still praying. I barked and then pawed at the soldier’s coat.

“He’s gone, fella. Nothing we can do I’m afraid.”

No…. no, look I beseeched him with a whine and continued to paw at the dead boy’s coat. Master stroked me but didn’t understand what I was trying to tell him. I barked loudly. The coat moved again, this time I barked forcefully, not prepared to stop until he looked.

“What on earth is the matter with you Reuben? He’s dead.”

No, no I insisted. Then he looked and saw the lapel of the soldier’s trench coat move. I stopped and cocked an ear; I could hear a noise coming from inside the soldier’s coat. I knew that sound, although I would never have believed it had I not heard it for myself. Master James heard it too and started frantically searching inside the dead soldier’s uniform. He carefully pulled out something small. He held it gently, and cupped it in both hands; he blew warm breath on it and rubbed it gently, a soft crying noise coming from between his fingers…. it was a kitten. I jumped up and down, trying desperately to get a better look, sniffing enthusiastically at his hands. He held the bundle of fur away from me and told me to get down. He placed the tiny creature inside his trench coat, and we quickly made our way back to the dugout.

Inside the dugout, London Charlie emerged from under the blanket where he shivered, pleased to see us return. He wagged his tail as we entered, and then he saw that master held something in his hands. He cocked his head and came to sniff whatever it was master held, hoping that it was food. Master James let us both sniff his hands but kept the little creature enclosed until he felt sure we wouldn’t attack it. Sounds of mewing came from behind his fingers.

“Gently now you two, do you hear?” he said firmly.

Slowly he opened his hands. The biggest pair of blue eyes looked out from behind his fingers. The little thing cried and shivered, her tabby-coloured fur was dirty and damp. The kitten was thin, she looked too young to be away from her mother. I had seen kittens many a time on the farm. They lived in our hay barn and earned their keep by hunting rats and pigeons who would get into the silos and contaminate the corn. London Charlie stood mesmerised by the little animal. He took a step back and looked at master James.

“It’s ok boy,” said master James.

London Charlie pricked up his ears, totally taken with her. Ever so gently he began to lick the little creature. I had never seen him take such care. The most boisterous and oafish of dogs was now the gentlest and kindest of souls. His strength was infinitely greater than hers, he could kill her with one bite should he choose, but I knew there and then that he would never hurt her, and he would always stand as protector and guardian.

Master had found an old ammunition crate to keep the kitten in whilst we were on patrol of an evening. London Charlie would always be first into the dugout on our return, rushing straight to the crate to check on his new charge and to wash her. He’d done a good job of cleaning her up, and we discovered that she had a white bib and chest, and two white front paws once the dirt had all been groomed away. Master James fed her beef tea from a teaspoon, and soon she was taking small chunks of bully beef from his hand. The meat was tough and took some chewing, but she managed it in the end. It seemed her appetite was growing as quickly as she was. The same could not be said for master James, as his coughing was getting worse, and most days he could barely face eating at all. I was worried for him. He began to grow thin and some days he didn’t leave his bed at all, save to feed us and the kitten and then to go out for duty. I kept vigil by his side, laying across him as he slept to see he stayed warm.

As the days passed, London Charlie and the kitten became inseparable. His whole world became about taking care of her. I on the other hand grew more and more concerned about master James. Master and I had returned from duty one night, sent back to the dugout early by the company sergeant when master James became too sick to stand up. The next morning, he lay in his bed shivering and sweating, and I was unable to stir him from his sleep. I pawed at the blanket, barking at him to get up, but it was all no use. London Charlie came over and sniffed master’s face, we both knew something was terribly wrong. London Charlie lay across him to keep him warm while I went for help. I couldn’t find master Alfred or Jess. I ran up to the communications trench, with no time to stop for my usual pats and scraps of bread and jam. I jumped over the men sat in the gangway, frantically searching in and out of the dugouts for Master Alfred. I stood barking at the top of my voice, but the men just laughed at me and tried to tussle me, thinking it was all just a game. Stupid, stupid men, no…. why didn’t they understand? Suddenly, Master Alfred appeared. He too thought it was a game at first, stroking my head as I barked. Jess sensed all was not well, and she too began to bark. Alfred dropped his hand, looking at Jess. I stood on point, looking down the gangway from where I’d just come. He realised something was wrong and picked up his rifle.

“What is it Reuben, what’s wrong fella?”

Jess and I took off in the direction of the reserve trench, master Alfred running behind.

In the dugout, London Charlie guarded our master. Master Alfred rushed to his bedside and tried to wake him, but he couldn’t. He told us to stay, and then he disappeared. We waited. Where was he, where had he gone… why wasn’t anyone coming? Master’s breaths were shallow and irregular, I pawed at the blanket.

“Wake up, please wake up,” I barked.

Master Alfred suddenly appeared again in the doorway, and this time other men came too. They were all talking but I didn’t understand what they were saying. They put my master on a stretcher and took him away. I sat in the gangway of the trench line and watched as they disappeared with him through the falling snow. Where were they taking him? I looked up at Master Alfred. He stroked my head.

“Now then Reuben, you and London Charlie will have to come and stay with Jess and me for a while. Don’t know how long it will be mind, and there isn’t much room, but I guess we’ll all just have to rub along together.”

He put a lead on me and picked up the old blanket that we used as a bed. He clipped a lead to London Charlie but as he went to leave, London Charlie refused to move. I barked at him to obey, but he pulled free of master Alfred’s grip and went and sat by the old ammunition crate in the corner. Alfred went over to the crate. London Charlie whined and scratched at the wooden box. He peered inside to see the tabby kitten sat amongst a bundle of rags. She stared up at the new visitor, not in the least bit perturbed by his presence. She blinked her big blue eyes and meowed.

“Well I never,” exclaimed master Alfred. “Where have you come from?” he said, lifting her up into the air.

The kitten looked around her, repeating her meows for food.

“It’s a wonder you haven’t frozen to death,” he said.

London Charlie licked her face; she batted his nose with her tiny paws.

“By rights, I should be getting rid of you… another mouth to feed,” he said to the kitten.

Master Alfred looked at the three of us and then he looked back at the kitten sat in his hand. She meowed.

“Guess you’ve no more wish to be here than the rest of us, eh? Well, I reckon we just have to look after each other.”

Just then a figure appeared in the doorway. I couldn’t see clearly because of the reflection of the light upon the falling snow, but I could see it was an outline of a dog. The figure lowered its head, creeping forward, a deep and sinister growl coming from its open mouth, it was Noah… he would kill the kitten for sure, he never did have any mercy. He launched at the tiny animal, knocking master Alfred off his feet. The kitten fell to the ground, dazed by the impact. Noah was upon her, but just as quickly and with equal ferocity, London Charlie was upon Noah. Jess rushed forward picking up the small kitten in her mouth, not to harm her, but to save her. She ran behind the crate with the kitten to shelter her from the two fighting dogs. They fought as fiercely as I had ever seen, blood coming from both their mouths, screeching and snarling ensued; teeth, fur, flesh, I could no longer tell who’s. I feared that there was only one way this would end, but then suddenly Noah submitted, whining on the floor, blood stained the white fur of the ruff of his neck. London Charlie backed away and stood looking at him, panting as he did so, blood dripping from his mouth, his face lacerated, his ear torn; Noah remained submissive on the floor. London Charlie turned to walk away, his neck exposed, I saw it in a flash, it was a trap. Noah launched to his feet, his mouth as wide as he could get it, aiming to lock onto London Charlie’s neck…. he was going to kill him. I leapt into the air, bringing my whole weight down upon his back, I knew I had just one chance, if I got this wrong, he would kill me for sure. His body buckled below my weight, taking him sideways off his feet. He swung his head around, a murderous look in his eyes, but my reactions were sharper, I had him pinned by his neck, my whole body holding him flat to the floor, winding him. I snarled and salivated, not letting my grip weaken.

“Leave here; leave here now, or I will tear you limb from limb.” I snarled.

I released my grip. Noah beat a hasty retreat from the dugout, blood dripping into the snow as he ran.

Two days later a battle-scarred London Charlie lay on the floor of the dugout with one small kitten swinging from his ear. She scrambled over his back, just to slide off and then pounce on his front paws, biting at his jowls in play. He licked her face, sending her bowling backwards as he did so. Today we were packing up and leaving. The campaign to secure the Somme region was to be disbanded. The weather had made fighting impossible, and with so many losses on both sides of the trench lines, it seemed that at last it had been decided that the battle had been too costly to continue. Men argued about whose victory it was. For all of us here in the trenches, it felt like there had been no victory for anyone.

Master Alfred packed his kit bag. He sat down and lit a cigarette, blowing smoke into the air as he stared at London Charlie and the kitten.

“What am I going to do with you lot….? Three dogs and a kitten... it’s a bloomin' menagerie.”

London Charlie wagged his tail. Master smiled and gave him a pat.

“She needs to have a name though boy, she’s got to have a name… it’s only proper. Never thought I’d see two dogs fight another to save a cat. You should have killed her by rights, after all, dogs and cats are supposed to be enemies…. but look at you, thick as thieves. You could teach us, humans, a thing or two. Hey, maybe there’s hope for us yet eh... That’s it. Hope…. we shall call her Hope.”

And with that we all got up and made our way out of the dugout and began the long walk up the trench line to the transport lorries, Hope wrapped up snug inside the lapels of master Alfred’s trench coat. Jess, London Charlie and I walked behind. Here we were, moving on; another day, another trench line, another battle…. in this never-ending war.

THE END.

Bilton Veterinary Centre

259 BIlton Road

Rugby

Warwickshire CV22 7EQ

Tel: 01788 812650

email: enquiries@biltonvets.co.uk

- Monday

- -

- Tuesday

- -

- Wednesday

- - -

- Thursday

- -

- Friday

- -

- Saturday

- -

- Sunday

- Closed