Why is Rat Bait toxic?

There are a few different types of rat bait

(rodenticide) used. The most common group used in the UK are anticoagulant rat

baits, which we will focus on here. They are potentially dangerous to all

mammals and birds, and are a common cause of poisoning in pets and wildlife.

Within this group there are different types, and while all carry a risk, some

are more dangerous than others.

How would my pet become poisoned?

Rat bait is often cereal based in order to make it tasty for the rodent. This also makes it appealing to a dog. Traditionally, people often lay rat bait in the open as well as inside buildings and often uncovered. Dogs that are off the lead, especially on farm land and around outbuildings, can get hold of the toxin this way. It is usually in blue pellets but there are also solid bait blocks available.

Cats are generally more discerning about what they eat, and rarely eat the bait. There is a theoretical risk posed by a cat eating mice that have been poisoned, but in reality we rarely see this happen. Rodents would probably have to be the main part of the cat’s diet in order to cause toxicity this way.

What is an anticoagulant?

Anticoagulant rat baits work by inhibiting vitamin K in its victim. Vitamin K is crucial in producing enzymes that are needed for a cascade of events ending in the formation of a clot, and so preventing life threatening blood loss.

There is often a lag period before any signs occur while the stores of these enzymes are used up. Once this happens the clotting cascade is halted and the next time a clot is needed, it cannot be produced. Bleeding, when it occurs, can then not be controlled or prevented by this normally protective mechanism.

Are all anticoagulant rat baits toxic?

All anticoagulant poisons are toxic, however some types are much worse than others.

The “first-generation” anticoagulants, such as warfarin, require multiple feedings to result in toxicity.

The “intermediate” anticoagulants such as diphacinone require fewer feedings than “first-generation” chemicals, and thus are more toxic to non target species like dogs.

The “second-generation” anticoagulants (brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone) are highly toxic to non-target species such as dogs, cats, livestock, or wildlife, after just a single feeding.

Why are these toxins allowed to be sold?

The demand for high quality food and concern for the health and safety of farm employees and livestock enforce the need for proper control of rodents.

A few years ago, the Campaign for Responsible Rodenticide Use (CRRU) was set up in response to concerns from government agencies, such as the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), about exposure of these toxins to wildlife, non-target animals and even people. A stewardship program was set up to improve best practice and to teach other ways to reduce rodent populations before resorting to rodenticides. From 2018 new regulations mean that amateurs are restricted on bait purchase. Farmers and growers will need a licence to buy the more lethal professional rodenticides, proving they are part of the scheme or have carried out training to use them. Securing the bait within bait boxes will help target the rodents, and not other animals or wildlife. Producers will not be allowed to use pulse baiting or permanent baiting. The concentrations of the strongest baits have been legally reduced.

These new regulations should not only help to reduce exposure to wildlife, but will also reduce the chances of your pet becoming exposed.

How will I know if my pet has been exposed?

In many cases ingestion has been witnessed, enabling swift action. However if this is not the case, signs are often delayed by several days, when the animal runs out of clotting enzymes. Signs depend where bleeding first occurs, so can be very variable. Nose bleeds, bloody faeces, small burst blood vessels in the skin, eyes, or gums, for example.

How is it diagnosed?

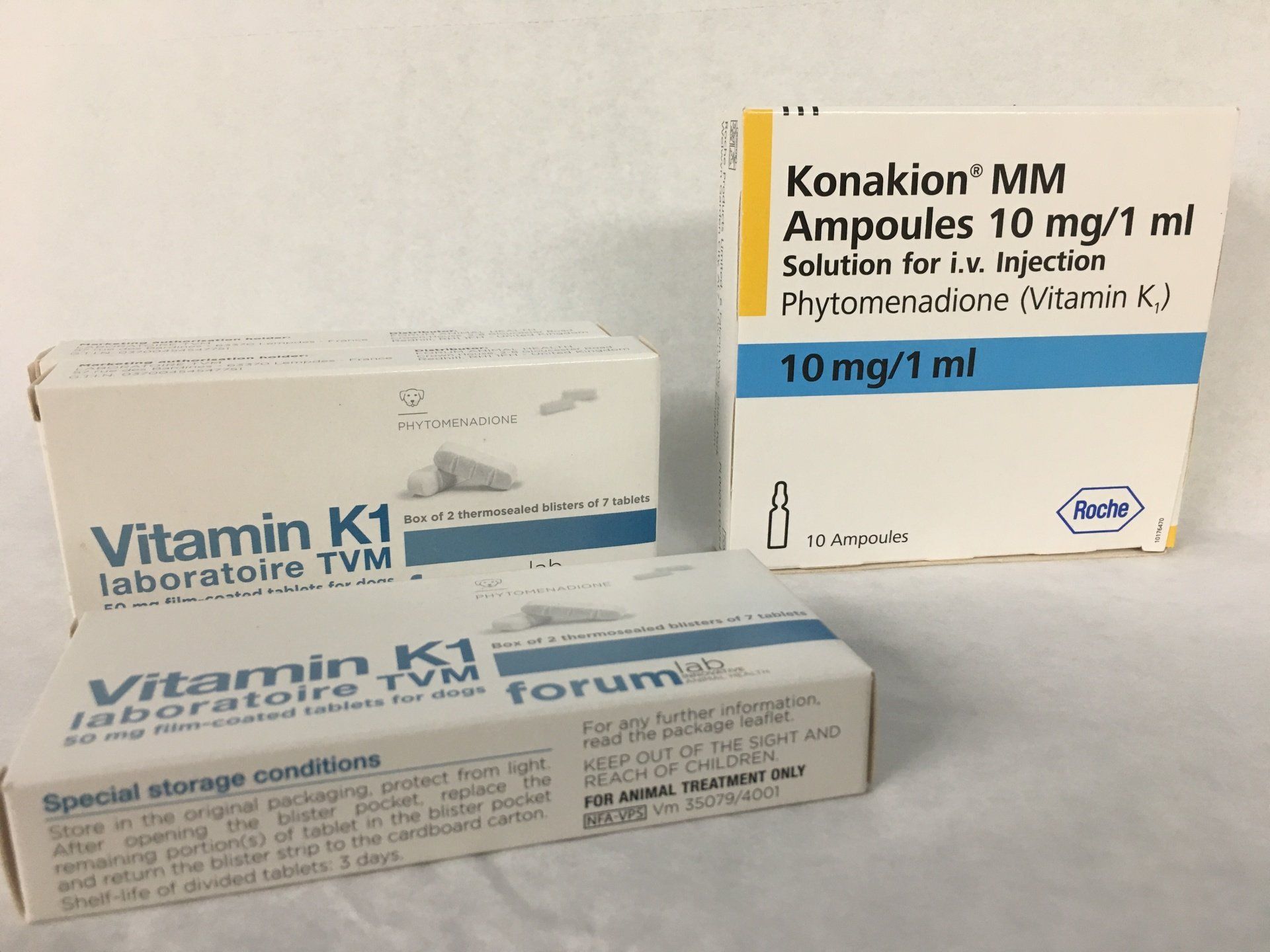

If ingestion was not witnessed, other causes of spontaneous bleeding must be ruled out such as lungworm, or other rare congenital clotting disorders. Clotting tests can be carried out on your pet’s blood, which help us confirm rat bait exposure. We treat this condition with Vitamin K, and their response to treatment is often used for confirmation.

What do I do if I think my pet has ingested some bait?

If ingestion was witnessed your pet will need to be seen immediately by our vets. It is important that you bring the packaging, or any information you have on the type of rat bait it was. The volume that was ingested, and the size of your pet will be important for making treatment decisions.

Often our vets will make your pet vomit to bring up any undigested bait. Given the active ingredient is absorbed very quickly, it may already be in their bloodstream. Giving activated charcoal may soak more toxin up, allowing it to pass through the gut and out in the faeces.

We use vitamin K orally, for varying lengths of time, depending on which toxin was ingested. If the toxin is unknown then we would give at least 3-4 weeks of vitamin K. Occasionally we may discuss blood transfusions if your pet is very anaemic. Despite treatment, in rare cases some dogs will not survive a large dose. We may perform tests to confirm clotting is sufficient before signing off treatment.

Rat bait is toxic through different mechanisms. Most commonly through its ability to stop your pet's blood clotting, which can in rare cases, or if left untreated, be lethal. New regulations and better control of these potentially harmful substances could significantly reduce the number of cases we see.

If you think your dog has been exposed to rat bait, call us right away before symptoms appear.